Dr Margie McEwen BVSc DACVAA MANZCVS

“Anaesthesia is an unusual speciality as it routinely involves deliberately placing the patient in a situation that is intrinsically full of risk.”

– Bould et al. 2007

This quote really resonates with me. If you consider a routine day in the clinic most of our actions are to heal, soothe, or repair. Yet every day, veterinarians and their nurse or technician colleagues place companion animals under anaesthesia. Most of the time, the risks are managed and the patients recover uneventfully.

This is an appropriate moment to pause. I’d encourage you to keep sight of the fact that during anaesthesia, we deliberately induce a state of physiological depression in our patients. We will cause this irrespective of whether our procedures are routine, planned or emergencies.

Cue the list of potential adverse effects: hypothermia, hypotension, hypoventilation, hypercapnia, increased myocardial sensitivity, the threat of respiratory acidosis, and others. Where opioids or alpha-2 agonists are involved we can add bradycardia or second-degree atrioventricular block to the list. But you already understand the complexities. I’d just take the sentiment one step further and emphasise that this is why every anaesthetic deserves your complete attention and your A-game.

Here are three ways to reduce anaesthetic risk in practice, extrapolated from the human literature.

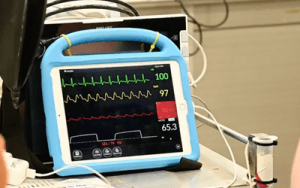

- Monitoring with appropriate equipment and dedicated personnel (Grubb et al., 2020)

I tell my students you can still practice high-level patient care without all the bells and whistles, and that monitors are only as good as the team using them. At a minimum, you should have equipment to measure SPO2, blood pressure, and body temperature.

Sometimes the person performing anaesthesia in private practice can be called away to check hospital patients, take phone calls or attend to reception. While I am so grateful to have worked with these brilliant multitaskers, having a dedicated person “on the head” really does improve patient safety. If this is achievable for you, please, by all means embrace this.

- Pain management

I’m board-certified in anaesthesia and analgesia. Yes, pain management is a welfare requirement, but have you thought about how it also paves the way for safer, smoother anaesthesia? A balanced or multimodal approach to analgesia allows us to reduce our reliance on inhalants and minimise the nociceptive responses which can disrupt anaesthetic depth, and improve patient recovery. Don’t forget your nerve blocks!

- Use checklists

If you’re not already using one, please, get a checklist. In fact, get several, because they really can reduce mistakes and save lives. One of my favourite studies comes from a World Health Organisation program in human hospitals (Haynes et al., 2009) where inpatient complications and deaths were measured before and after the introduction of surgical checklists. There was a 47% reduction in deaths and a 36% reduction in inpatient complications associated with the checklist’s implementation.

I don’t think it’s a big stretch for veterinary professionals to acknowledge the clinical challenges of veterinary anaesthesia, or to engage in continuing professional development in this field.

Today, I wanted to shine a spotlight on other factors within our control – the human element. We have the opportunity to allocate our resources in a way that reduces risk. Assign staff to perform the tasks ahead, and use appropriate equipment (with checklists!). And because I can, it never hurts to mention analgesia again.

To join Margie’s online training in veterinary anaesthesia, see https://vetprac.com.au/on_

Dr Margie McEwen is an Australian veterinarian, US board-certified veterinary anesthesiologist and Director of VetPrac. VetPrac provides online and face to face continuing education for veterinarians, veterinary nurses and veterinary technicians.

References

Bould, M. D., Hunter, D., & Haxby, E. J. (2007). Clinical risk management in anaesthesia. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, 7(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkm010

Grubb, T., Sager, J., Gaynor, J. S., Montgomery, E., Parker, J. A., Shafford, H., & Tearney, C. (2020). 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats*. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 56(2), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.5326/jaaha-ms-7055

Haynes, A. B., Weiser, T. G., Berry, W. R., Lipsitz, S. R., Breizat, A. H. S., Dellinger, E. P., Herbosa, T., Joseph, S., Kibatala, P. L., Lapitan, M. C. M., Merry, A. F., Moorthy, K., Reznick, R. K., Taylor, B., & Gawande, A. A. (2009). A Surgical Safety Checklist to Reduce Morbidity and Mortality in a Global Population. New England Journal of Medicine, 360(5), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa0810119

Palomba, N., Vettorato, E., de Gennaro, C., & Corletto, F. (2020). Peripheral nerve block versus systemic analgesia in dogs undergoing tibial plateau levelling osteotomy: Analgesic efficacy and pharmacoeconomics comparison. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 47(1), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaa.2019.08.046